The tongue is responsible for our sense of taste. See this post for tongue anatomy.

The surface of the tongue is covered in more than 10,000 tastebuds, small chemoreceptors discovered in the 1900s that provide us with the sense of taste by picking up on five different types of chemicals.

Taste is the brain’s interpretation of chemicals, called tastants, that trigger these receptors. The basic chemical components are found in foods, toxins, and other ingested matter. Unappealing tastes are usually associated with toxins, as this is a defense mechanism preventing consumption.

The chemicals bind their particular receptors and initiate signaling that travels through the nervous system to the brain, where they are interpreted.

Chemicals sensed by the tongue

| Taste | Chemical |

| Salty | Ions (e.g., sodium) |

| Sweet | Sugars, ketones, aldehydes, some amino acids |

| Sour | Acidic compounds |

| Bitter | ATP and reaction byproducts |

| Umami/savory* | L-glutamate/glutamic acid |

Tastebuds and chemoception

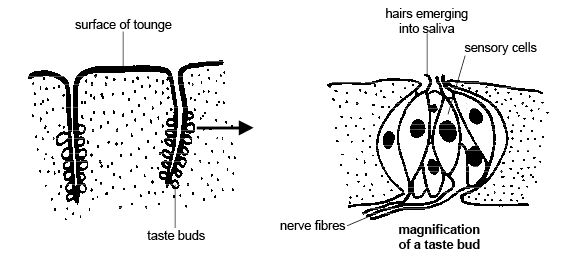

The tastebuds are the small, visible bumps on the tongue. They are actually nerve endings within a protective envelope on a short stalk and are also called gustatory cells.

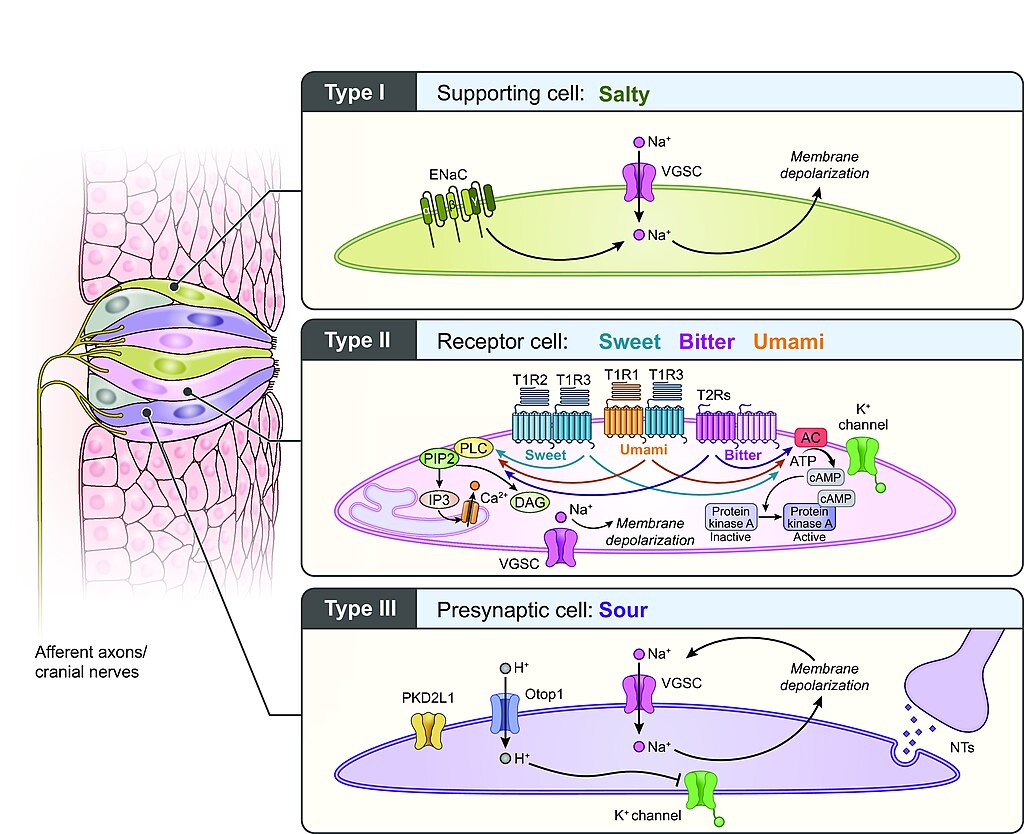

Tastebud nerve endings conduct signals through ion channels or G-protein coupled receptors, depending on the type of chemical being detected.

The traditional flavors of salty and sour are transmitted by ion channels that generate an action potential. Saltiness is perceived when ions, including sodium, magnesium, potassium, and often calcium, are present in the saliva or on the tongue. The receptors respond more strongly to sodium, making it seem saltier. Sour is perceived when acidic compounds activate hydrogen ion channels, which depolarizes the gustatory cells. This allows the two tastes to be different, though the signals are relayed in a similar manner.

The traditional flavors of sweet and bitter are relayed by G-protein coupled signaling. Sweetness is a response to sugars and other molecules, including aldehydes, ketones, and the amino acids glycine, alanine, and serine. The bitter sensation has been found to have a genetic component; some people taste certain foods as bitter, broccoli for example, while others do not, presumably due to a difference in the number of receptors. This may explain why it was the last of the four to be added to the common list, by the Greek philosopher Democritus.

Most naturally bitter compounds are toxic, which may indicate an evolutionary component to the taste. However, some medicines, such as the anti-malarial quinine, and common foods, such as coffee, beer, unsweetened chocolate, and citrus peel, are also bitter. Recent research has found that the bitter taste may be a response to chemical reactions rather than direct ingestion of a tastant, and they are found in areas of the body outside the oral cavity.

The fifth tastebud

A French chef, Escoffier, became famous in the 1800s for creating dishes that tasted like none of the four taste sensations. This new taste came from his use of veal stock. Asian cooking has used this same flavoring as a fundamental taste in their dishes for a long time. A Japanese chemist, Kikunae Ikeda, published his findings about the key chemical from seaweed broth in the journal of the Chemical Society of Tokyo in 1908. The chemical was glutamic acid.

Glutamic acid, or its basic form glutamate, activates G-protein coupled signaling. This amino acid is often found in fermented or aged foods. The taste is commonly referred to as meaty or savory, but the name given by Ikeda 100 years ago was umami. In 2002, scientists found that there is indeed a fifth tastebud, one that senses L-glutamate. They gave the flavor the official name of umami.

Innervation

Two cranial nerves carry taste signals from the tongue through the nucleus of the solitary tract in the brainstem: VII (facial nerve) and IX (glossopharyngeal nerve). The vagus nerve (X) also carries taste information to the brain, but it gains that information from the back of the mouth.

These nerves send taste signals to the thalamus and somatic sensory cortex (the gustatory cortex), and then to the limbic system (amygdala and hypothalamus) with information on smell.

Disclaimer: This page is for informational and learning purposes only. It is not meant to diagnose or treat any medical condition and should not be used in place of speaking with a medical doctor or seeking treatment.

Aliconia Publishing, LLC and the author make any and all attempts to ensure the accuracy of the presented facts. If you find an issue with any information on these pages, please use the Contact page to alert us. The content is subject to change based on new information or to be updated with additional facts. The date of last change is stated under the main header.

Discover more from Just Facts

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.