Updated Sept. 3, 2020

A congenital disease is a defect or disorder that is present from birth. Congenital heart disease includes a variety of defects in the heart tissue or valves due to improper fetal growth or problems in the closure of fetal vessels after birth.

Fetal Heart Anatomy

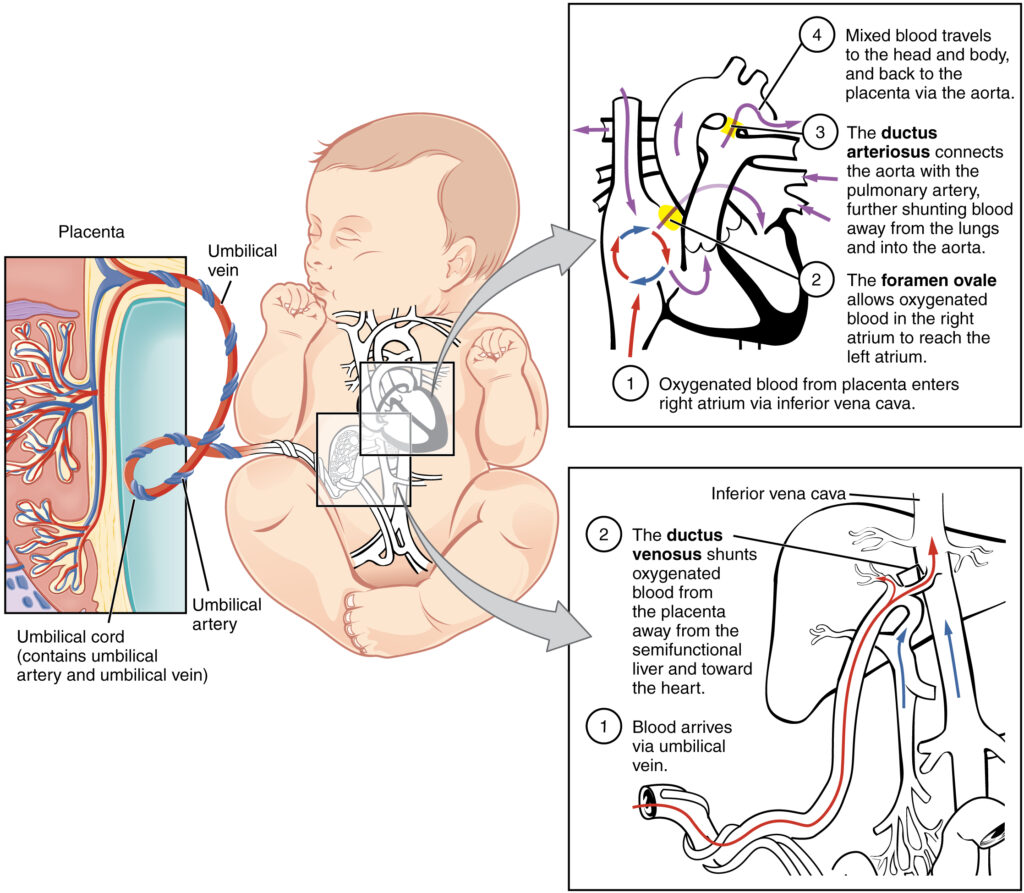

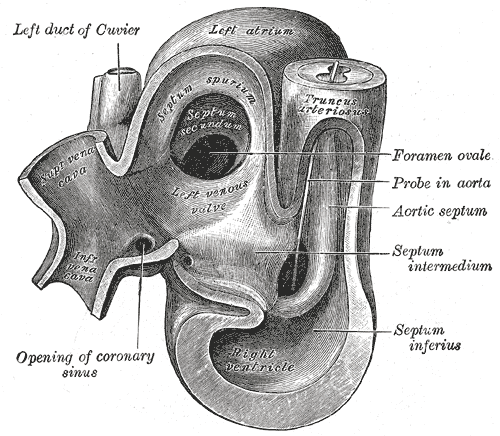

The fetal heart is not identical to an adult, or even newborn, heart. Because a fetus receives oxygen from the mother’s circulation and does not use its lungs, the fetal circulation does not include the pulmonary vessels. A hole called the foramen ovale in the atrial septum, the wall between the right and left atria, allows blood to pass directly from the right side of the heart to the left. The fetal heart also has an extra vessel alongside the great vessels, the aorta and pulmonary artery, which align and twist around each other during gestation. The vessel is called the ductus arteriosus.

Congenital heart defects are usually recognized in infants shortly after birth because of the importance of circulation in sustaining life, and the change in palor that presents with cyanotic (lack of oxygen) defects. The Merck Manual for Healthcare Professionals reports that approximately 1% of live births has a congenital heart defect, and it is a leading cause of infant mortality. These defects, or anomalies, tend to form in the first 10 weeks of fetal life.

Types of Congenital Heart Anomalies

Left to Right Shunt

A left to right shunt is a passage allowing blood in the heart to bypass being pumped through the aorta and returns to the right side. The most common types of congenital heart disease are left to right shunts caused by holes in the ventricular septum due to defects in the membrane along the intraventricular ridge. The holes usually close spontaneously throughout childhood.

Another left to right shunt is the improper closing of the foramen ovale. When a baby takes its first breath of air outside the womb, a flap closes over the foramen ovale due to the pressure. If this does not occur, then blood is able to seep through the atrial septal defect.

The size of the shunt will determine if, and to what extent, symptoms occur. The pressure within the pulmonary artery or ventricle may increase, depending on the type of left-to-right shunt. High pressure in the ventricle could result in ventricular hypertrophy, and high pressure in the pulmonary vessels can affect lung function.

Right to Left Shunt

A right to left shunt bypasses the pulmonary circulation and results in what is referred to as a “blue baby,” that is a lack of oxygen to the body resulting in cyanosis, and the pink tinge is lost from the baby’s complexion. The shunt occurs as either a transposition of the great vessels or the Tetralogy of Fallot, which is the most common cyanotic congenital heart disease.

Transposition of the great vessels occurs when the aorta and pulmonary artery end up being attached to the wrong side of the heart when they do not twist properly during growth. Deoxygenated blood is then pumped out through the aorta without making it through the pulmonary circulation or the left ventricle.

The Tetralogy of Fallot is so-named because it consists of four things:

- Ventricular septal defect

- A septal defect with a dextraposed aorta overriding the ventricular septal defect, thus the blood is pumped directly out of the heart from the right side

- Right ventricular hypertrophy, which is an enlarged right ventricle, often caused by increased workload.

- A narrowed, and thus obstructed, pulmonary artery or valve, which would impair deoxygenated blood from getting to the lungs

These characteristics result in a cyanotic condition because blood cannot get to the lungs but is still pumped out to the body.

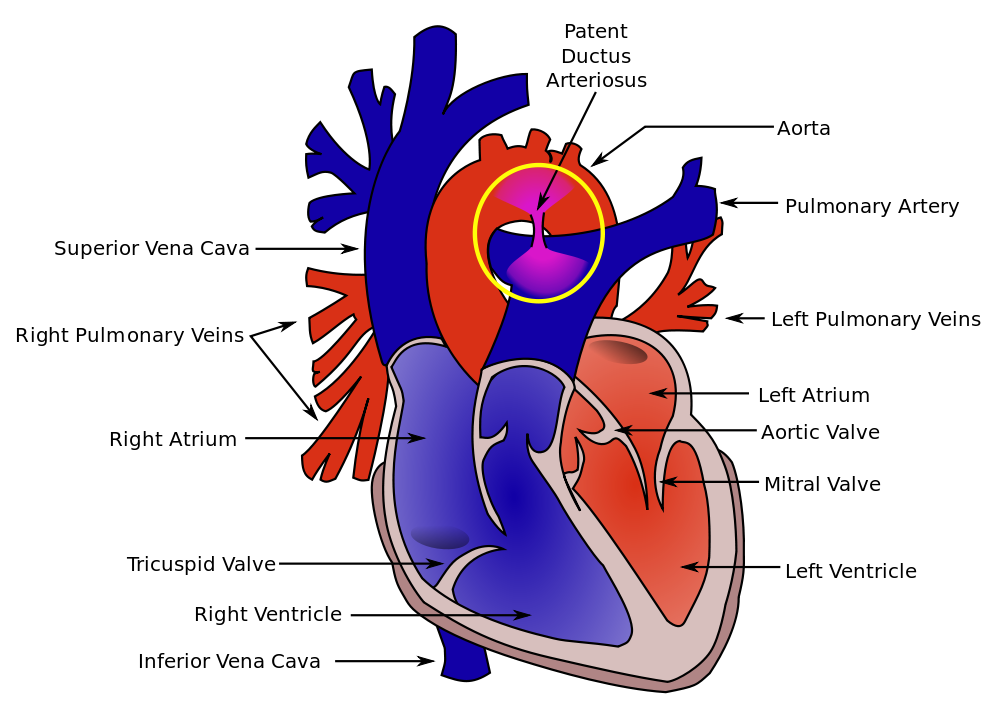

Patent Ductus Arteriosus and Coarctation of the Aorta

Two other types of congenital defects are patent, or persistant, ductus arteriosus and coarctation of the aorta. Coarctation is a narrowing of the vessel. It can occur either in infancy (i.e., preductal) or as an adult (i.e., postductal). A narrowing prevents the blood from properly pumping out to the body.

After birth, the ductus arteriosus constricts in response to increased arterial oxygen. It is usually nonfunctional within 1 to 2 days in healthy infants. Infants who experience hypoxia (a lack of oxygen) may have delayed closure resulting in blood being shunted from the pulmonary artery to the aorta, exacerbating cyanosis and hypoxia.

Treatment of Congenital Heart Disease

Some congenital heart lesions, such as ventricular septal defects, heal on their own in the absence of other defects or disease. Other congenital lesions, and more severe cases, may require surgical intervention to correct the defect and restore proper circulation through the heart and lungs or replace the heart with a transplant.

A lack of blood oxygenation can lead to brain damage and other organ damage, and eventually death. The heart may attempt to compensate and be damaged if defects are not corrected in a timely manner.

Sometimes the defects are obvious, like cyanosis, sometimes there are audible heart murmurs to clue doctors into the potential problem within the baby’s chest. There may also be irregular rhythms or pain as the condition affects the heart over time. However, it is not always easy to know for sure that there is a problem with a baby’s heart until it has advanced, so once identified by a doctor congenital heart defects are usually treated immediately.

Disclaimer: This page is for informational and learning purposes only. It is not meant to diagnose or treat any medical condition and should not be used in place of speaking with a medical doctor or seeking treatment.

Aliconia Publishing, LLC and the author make any and all attempts to ensure the accuracy of the presented facts. If you find an issue with any information on these pages, please use the Contact page to alert us. The content is subject to change based on new information or to be updated with additional facts. The date of last change is stated under the main header.